There has been a very active discussion occurring on the

Pilots of America web board the last couple of weeks regarding a

Hold-in-Lieu-of-Procedure-Turn (hereafter HILPT) published on an approach chart

in southern Oklahoma. Sadly, as is the case with many online forums, the

discussion has degraded into name-calling, insults and other unproductive and

uneducational matters. So I'll try to break it down here.

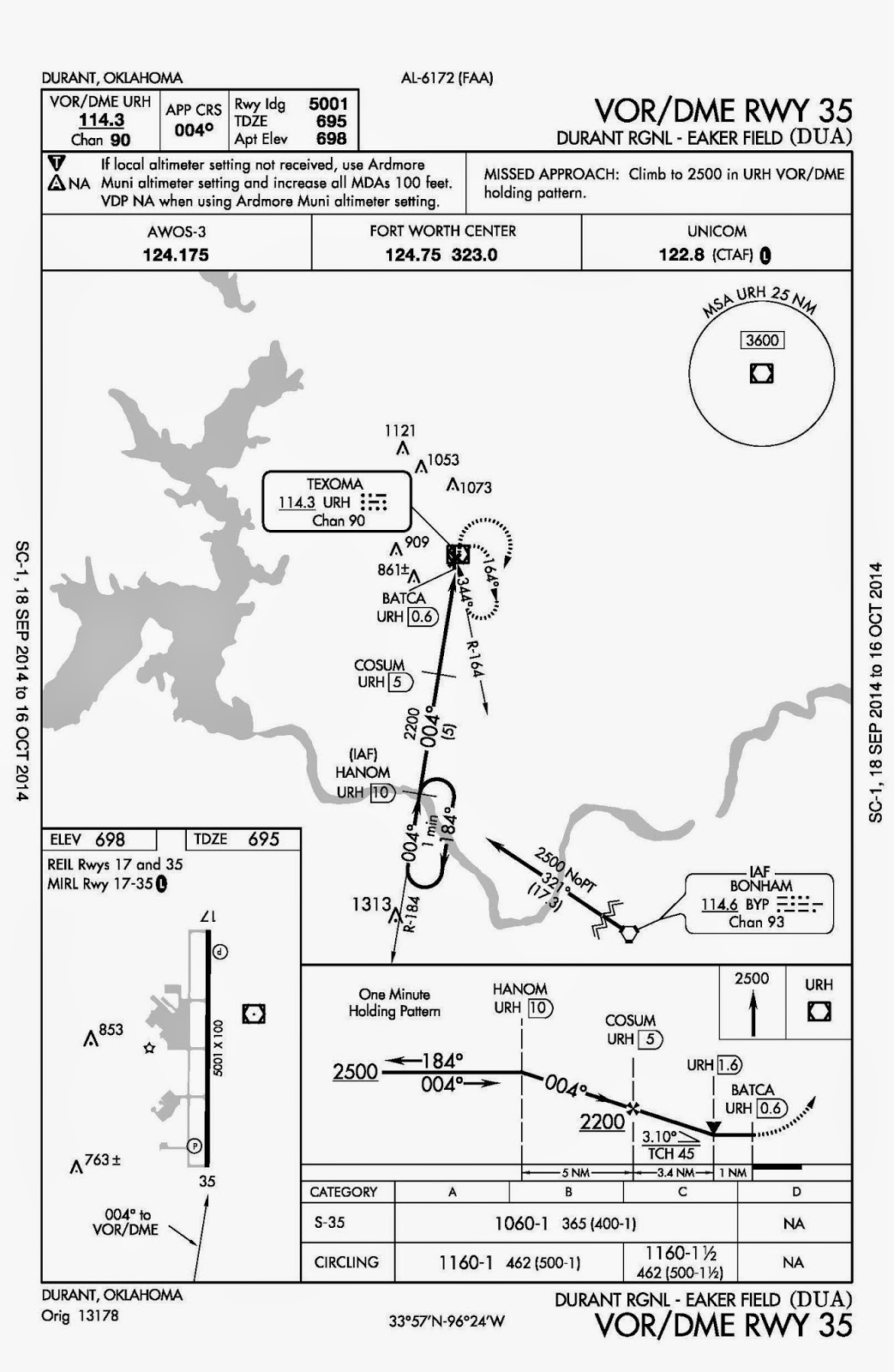

The approach in question is the Durant, OK (KDUA) VOR/DME

RWY 35.

Notice there is one published way for a non-GPS-equipped

aircraft to enter this procedure without receiving radar vectors to final. That

aircraft would start at the BYP VORTAC IAF, fly the BYP-321 radial until HANOM,

turn right, then proceed inbound to the URH VOR/DME on the URH-184 radial.

There is a HILPT published at HANOM, but since the route from BYP is labeled

NoPT, you would not fly the HILPT coming from that direction.

Well, then from what direction DO you fly the HILPT?

Seems like an easy answer, that you'd fly the HILPT if

you were coming at the approach from the north - you'd fly to the URH VOR/DME,

then outbound on the 184 radial to HANOM, execute the HILPT and proceed

inbound. Except it's not quite that easy, for one main reason:

There is no published segment from URH to HANOM.

Sure, there's a published route from HANOM to URH, but

that's not the same thing. A route from URH to HANOM would be properly

identified by a thin line as a feeder route. Note that the indication "R-184" below the HILPT does not indicate a route, it is simply showing what radial the final approach course is on. A route would be indicated by an altitude, a course, and a distance. So what is missing here is a charted,

evaluated, and published route from URH to HANOM. Note that courses on

instrument approaches are one-way, not two-ways like on most airways, and aren't

meant to be flown backwards. This is why each segment of an approach has a

directional arrow.

This is especially confusing because the URH VOR/DME is right on an airway - V63 - so it would be a logical place to have a feeder. Would it be possible to fly that route, from URH to HANOM

and turn around? Of course - any instrument pilot should be able to do it with

no problem. But from the way this procedure is charted, that exact route has

not been evaluated for obstacles, even though the route the other way has been

(the intermediate and final segments).

Why does this matter? It seems from looking at it that

flying from URH to HANOM at an altitude of, say 2500 should work just fine. The

reason has mainly to do with the difference in size of the areas evaluated by

TERPS for intermediate and final segments versus a feeder route; the area

evaluated for a VOR final being much narrower than for a feeder route. (At the

VOR, the final is 1nm each side of center, whereas the feeder is 4nm each side

of center, not considering what are known as "secondary areas" (see

my 3/30/14 blog post for more about secondary areas.)

Let's say you're approaching the VOR in such a way that

you need to make a 90 degree turn to go outbound on the uncharted

"feeder" route from URH to HANOM. An actual feeder route, being

wider, allows for you crossing the VOR, then beginning your turn, with enough

area to contain the turn radius. A final segment used in reverse would not have

this, as the area is much smaller (and turns to line up on final are much more

restricted in terms of heading change for this reason). Might not be a problem

in a 172, but in something faster it could. What if there is an antenna tower

or mountain off to the side of final?

Sometimes a picture is worth more than 1000 words. This

is probably such a situation:

This diagram shows a notional view of the areas evaluated

for this approach. Since the area from HANOM to URH has been evaluated as a

final approach segment, it's pretty narrow. But if an aircraft inbound from the

east crossed the VOR and made a turn to proceed outbound on the final approach

course, it could easily exceed the boundaries of the evaluated area. At 150

knots, a standard-rate turn results in a turn radius of about 0.8 nm. The final

approach area is only 1.0 nm wide at the VOR, so while it seems to fit, that's

only in an ideal situation. Adding in a tailwind that will increase turn

radius, a slightly delayed start of the turn, and imperfect pilot technique

means you rapidly run out of safety margin. What's outside of that area? Could

be an antenna tower, could be a mountain, or it could be level terrain as far as the eye can see. There's no telling, but the published altitude doesn't

reflect that because it wasn't part of the evaluation.

Compare that to the case if a feeder route was published

from URH to HANOM. The feeder route, being much wider for exactly this reason,

easily accommodates the turn radius:

So, if we can't fly from URH to HANOM for the HILPT, and

if the only published route from BYP to HANOM is a NoPT segment, what's the

purpose of the HILPT in the first place? There is none. I speculate that the

HILPT is charted correctly, but that a feeder was erroneously left off during

publication. This has been brought to the FAA's attention, so it will be

interesting to see their response.

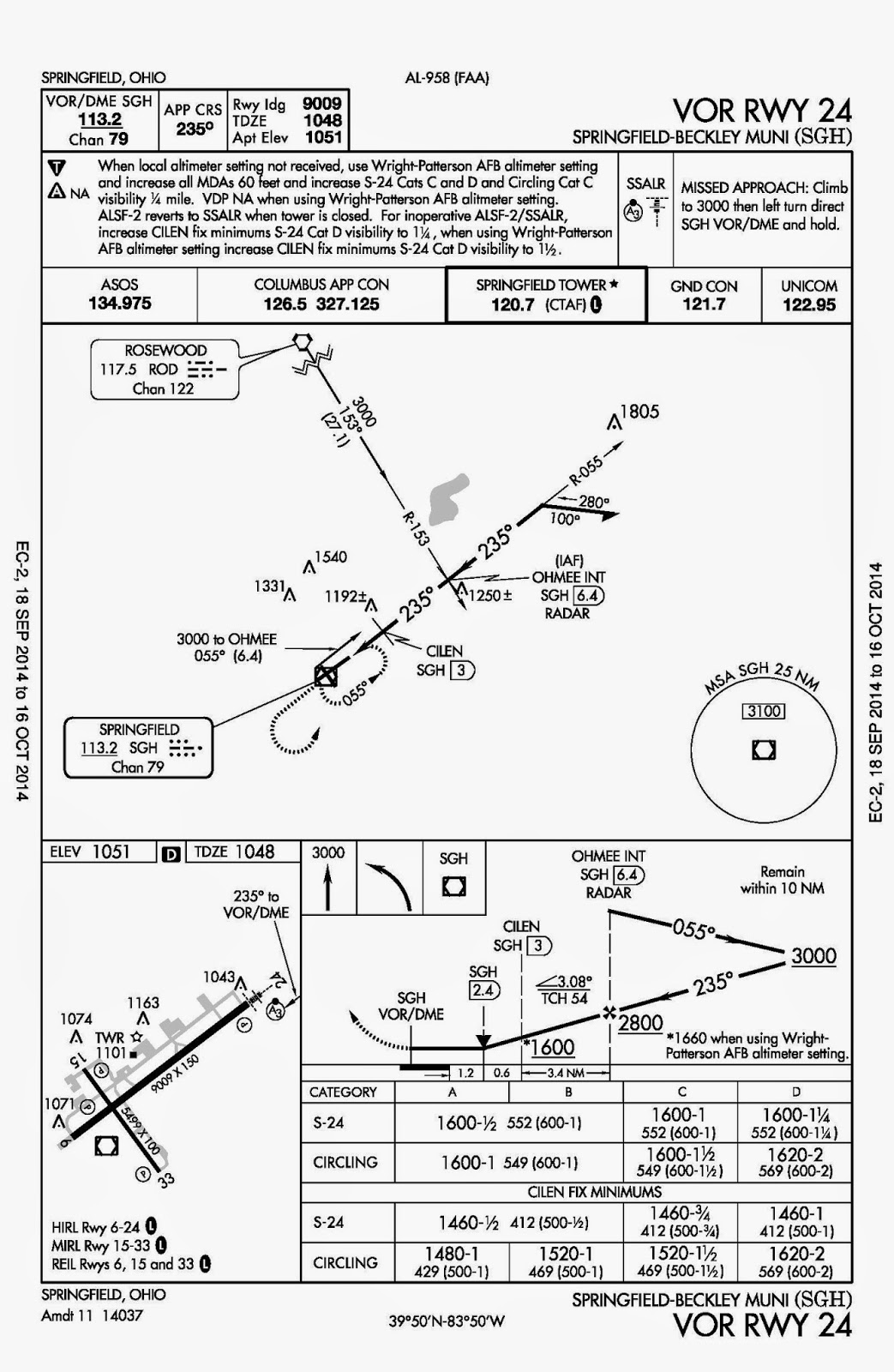

An example of a similar procedure that has the

feeder and the Procedure Turn (though not a HILPT) charted is the Springfield, OH VOR RWY 24. Notice the thin line from the SGH VOR labeled "300 to OHMEE, 055 deg, (6.4)". It has all the necessary data to serve as a feeder route and has been evaluated and charted. Thanks to a blog reader (and former student) for providing this example!